Along with the coronavirus pandemic, America’s epidemic of racism has taken a disproportionate number of black* lives.

We watched the Black Lives Matter protests erupt in early June, after another white police officer kneeled on the neck and suffocated another black man—George Floyd. We have heard the pain and the rage of 400 years of violence committed against black Americans. The unacceptable violence inflicted upon black and brown bodies in the United States comes in many forms. It is a product of a historical and current systemic racism, part of every institution we can think of—the law enforcement and prison system, education, health care, the workplace, and the financial and economic systems underpinning the substantial racial inequality we still have in America today. The individual racist attitudes of white people, in particular, also inflict harm on Black/African American and other people of color, who personally experience racism to varying degrees of severity from thoughtless remarks to extreme racial hatred and violence. It is more than time that, for those of us who are white (or white passing), we reflect on our privilege and take action against the system that privileges us in many ways as it causes harm to the opportunities, happiness and safety of people of color.

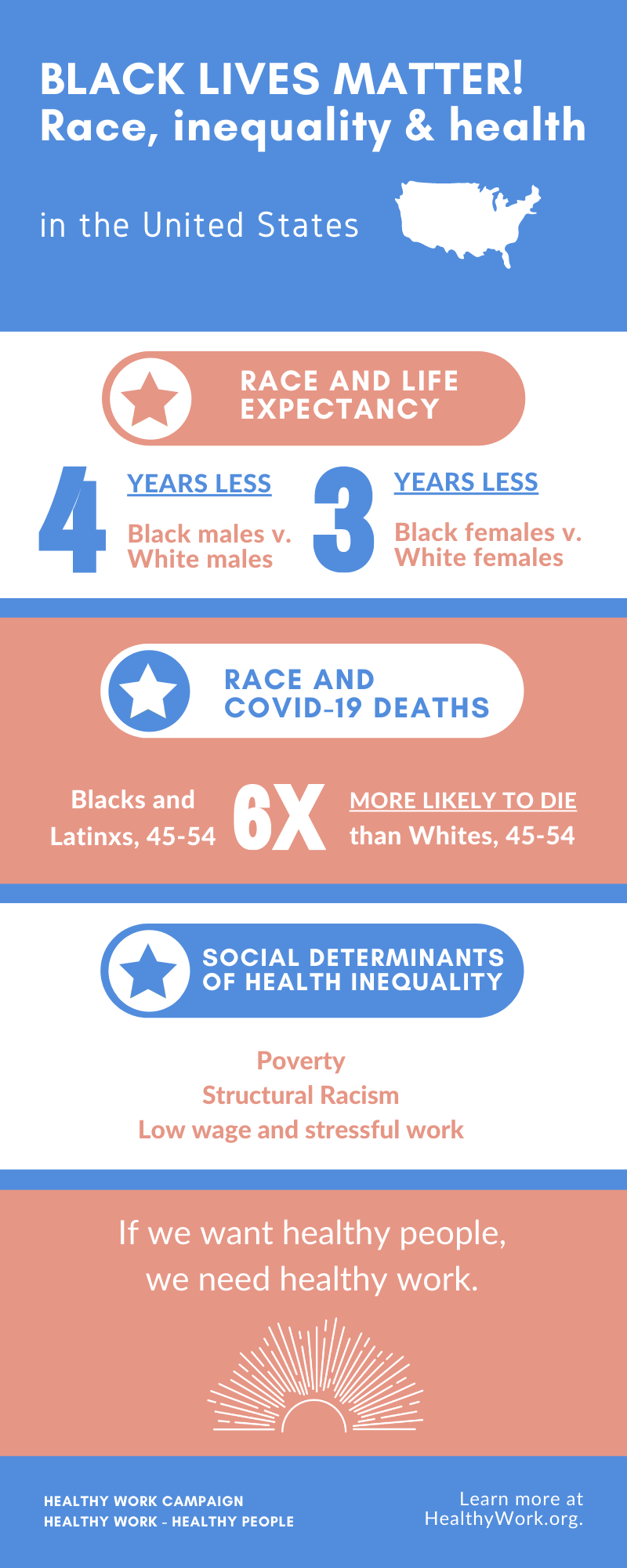

Whether structural racism or personal racism, the effects are a form of cumulative exposure to stress for black people which accounts for a sizable portion of the health inequalities (poor health and lower life expectancy) that black Americans experience compared to white Americans. A black man will live four years less than a white man, and a black woman will live three years less than a white woman. African Americans, on average, experience higher rates of hypertension, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD). While these are often blamed on individuals’ lifestyles, they are in fact influenced by social determinants of health—poverty, low-earning and stressful work, and racial/ethnic discrimination.

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, tying calls for racial justice with economic justice. African American people disproportionately live below the poverty line compared to whites (27.4% compared to the overall US poverty rate of 15%). In 2010, the median wealth (net worth) for black families was $4,900 compared to $97,000 for white families! Thirty-six percent of blacks were employed in low wage jobs compared to 23% of whites.

The Healthy Work Campaign raises awareness about the quality of these low-wage jobs, most often occupied by people of color. Low wage work is not only economically inadequate in terms of affording average rents, saving for the future, or affording healthy food (many low wage workers rely on food stamps to feed their families), it also exposes workers to more dangerous working conditions (including high levels of work stressors), inconsistent schedules, disrespectful treatment and discrimination. There is a large body of research showing that exposure to work stressors such as high job demands and low job control, effort reward imbalance, job insecurity, long work hours, bullying and discrimination, increases the risk for high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, mental health disorders, and cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Now, during this global pandemic, Black and Latinx people of all ages in the U.S. are dying from COVID-19 at markedly higher rates than whites. Among those aged 45-54, Black and Latinx death rates are at least six times higher than for whites! Part of the reason for this mortality gap is that Black and Latinx people are, as described above, more likely to have underlying, chronic health conditions including diabetes, obesity, hypertension and CVD. Many are also “essential workers”—transit workers, food service workers, grocery workers, meatpacking workers, hospital janitors and other custodial staff, and warehouse workers, and are not only more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 as part of those jobs, but have also been exposed to the stressful working conditions associated with these jobs. They are also more likely to work in jobs that are not easily worked from home, live in multigenerational households, and make greater use of public transportation which all increase the risk for exposure to COVID-19. Black and Latinx workers are also more likely than white workers to have seen retaliation from employers against workers in their company who have raised COVID-19 related health and safety concerns, and to have unresolved COVID-19 related concerns at work.

Racial justice also means protecting essential workers by providing healthy work. Healthy work means safe work including greater availability of PPE’s, and a guaranteed right to sick leave so that people are not forced to come to work when ill. Now more than ever, healthy working conditions matters for black lives and for all workers of color. Please join us and seriously address policies and practices in the workplace that increase diversity and the prevalence of #healthywork particularly for people of color and for all working people.

*We acknowledge that not all people with African heritage in the United States identify as African American (for instance, some recent immigrants). We are also aware that some with African ancestry prefer “Black” with a capital “b” over “black” with a lowercase “b.” We honor and use all of these nuanced identities in this article.